SUDAN WAR, Explained

Geopolitics of the Largest Humanitarian Crisis

January 4, 2026

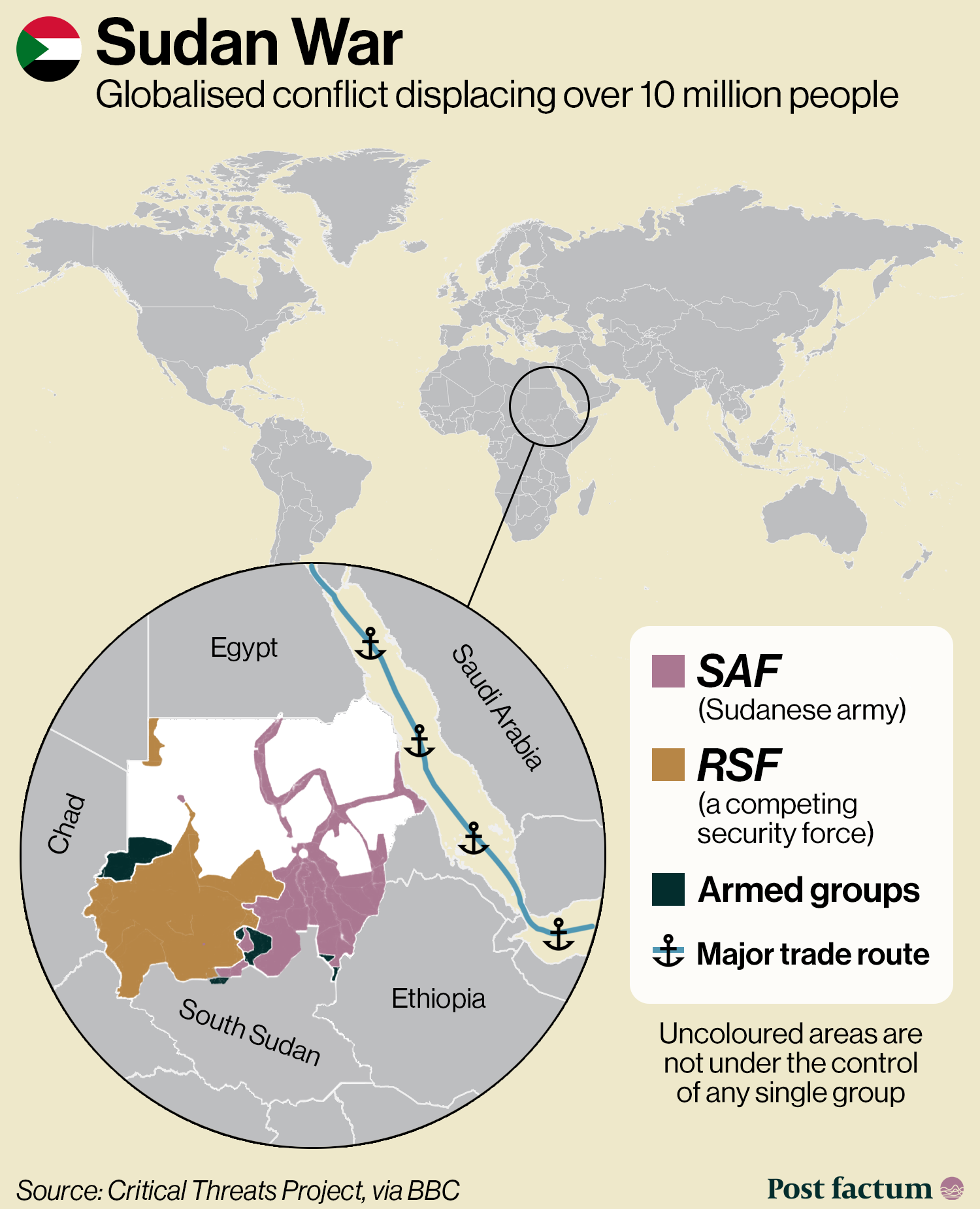

A civil war broke out in Sudan in 2023 over the control of the country and its natural resources, especially oil and gold.

Sudan is located on the Red Sea, where 10-15% of global trade is shipped.

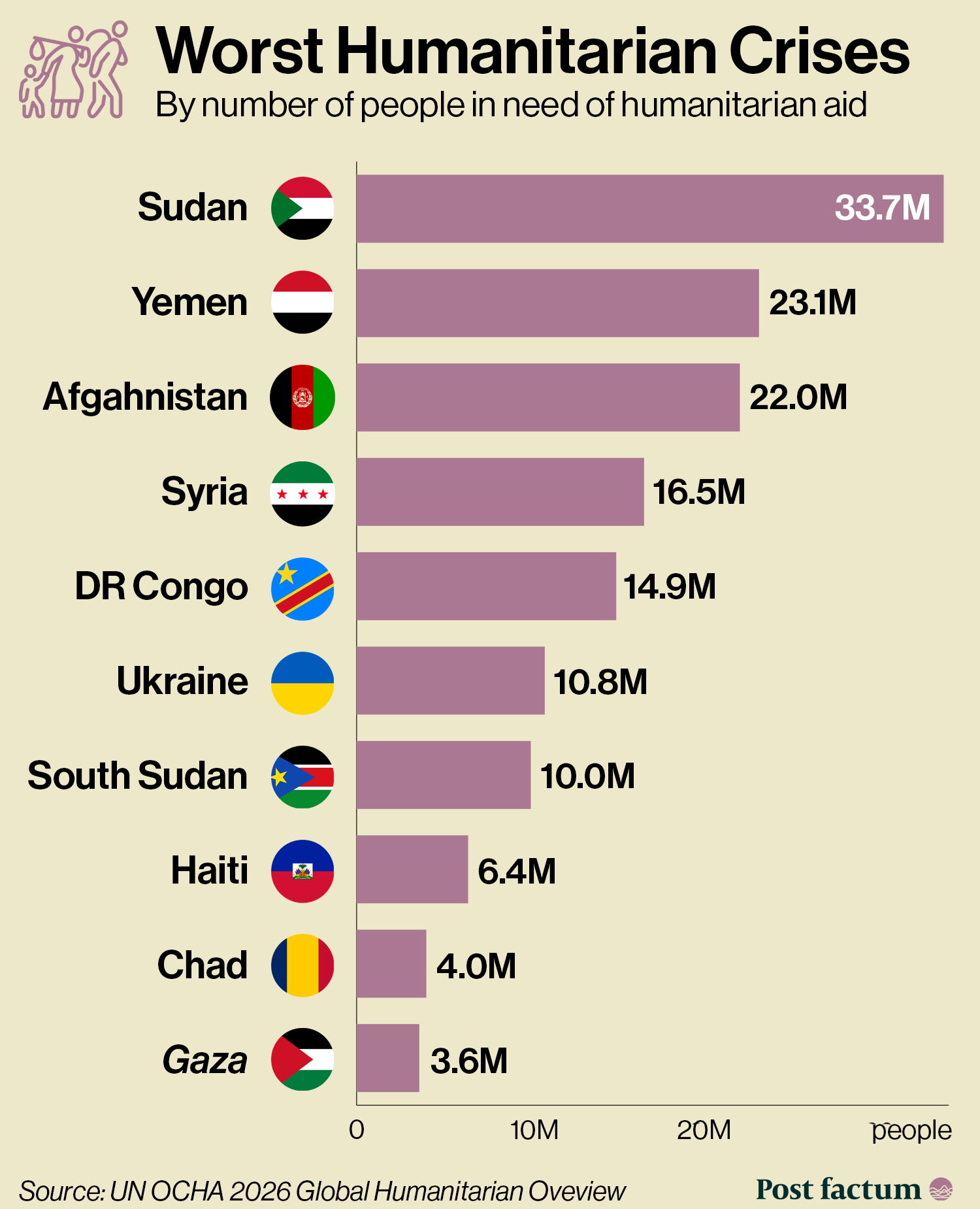

The war has caused the largest ongoing humanitarian crisis, with over 30 million people in need of aid in 2026.

Multiple foreign actors are involved in the conflict, including Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Russia and Türkiye.

Why did the war start?

After gaining independence from the UK and Egypt in 1956, Sudan experienced two civil wars.

In 1989, Omar al-Bashir seized power and set up a dictatorship.

Al-Bashir promoted an independent militant group that he used to suppress ethnic and political protests.

This group was later reformed as the RSF (Rapid Support Forces), an official security force competing with the army.

Sudanese Arabs account for 70% of the population, with non-Arab communities mostly in the south and west.

In 2003, a revolt over the treatment of non-Arabs started in the eastern Darfur region.

Al-Bashir responded with a brutal ethnic cleansing, killing around 200,000 people and terrorising the local population.

In 2011, South Sudan gained independence in a civil war. Sudan lost 75% of its oil reserves, starting an economic crisis.

In 2019, al-Bashir was overthrown in a revolution organised by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The leaders of the SAF and the RSF promised to oversee a transition to a civilian government.

The two leaders failed to reach a compromise.

One of the main issues was the integration of the RSF into the regular Sudanese army.

In April 2023, tensions escalated into a new civil war.

The civil war worsened the humanitarian crisis in Sudan.

Around 14 million people have been displaced, with 3.5 million seeking refuge in neighbouring countries like Egypt, South Sudan, Chad and Libya.

Over 11 million people are internally displaced within Sudan.

The precise number of deaths is unknown, with some estimates above 150,000 fatalities.

Approximately 400,000 people risk starvation, while tens of millions are affected by famine.

The SAF and RSF are both blocking food and medical supplies on some occasions.

33.7 million people, over half the population of Sudan, are in need of humanitarian assistance.

A third of all hospitals are no longer working due to attacks and supply shortages.

Drivers of the conflict

There is no major ethnic or religious division between the SAF and RSF.

Both consist of Sudanese Arabs and Arabised African ethnic groups.

The RSF emerged from a reorganisation of the Janjaweed militias.

The Janjaweed committed genocide against non-Arab communities in Darfur, along with some of al-Bashir’s regular army.

The main cause of the current conflict is economic.

Sudan is rich in natural resources, especially oil and gold.

Sudan exported $1.3B worth of oil in 2023.

Most of its oil fields are in the south, near the border with South Sudan.

Today, most of Sudan’s oil fields are under RSF control.

However, SAF controls the country’s main refinery in the capital, Khartoum.

Sudan exported $1B worth of gold in 2023.

About as much of Sudan’s gold is smuggled illegally.

The UAE imports most of Sudan’s official and unofficial gold exports, as a key player in gold refining.

The regime of General Haftar in parts of Libya sometimes acts as a middleman for illegal trade and money transfers to and from Sudan.

RSF and SAF both use oil and gold profits to finance themselves.

The RSF commands around 100,000 troops, while the SAF has around 200,000 soldiers.

The SAF controls around 60% of Sudan, mostly the northern and eastern regions of the country.

The RSF controls most of the western regions.

In March 2025, the SAF recaptured the capital after nearly two years under RSF control.

In late October 2025, the RSF took control of El-Fasher, the last city held by the SAF in Darfur, after an 18-month siege.

Thousands of locals were executed by the RSF, with tens of thousands fleeing the city. Exact casualties are not yet known.

International involvement

Both the SAF and the RSF rely on foreign support.

In exchange for military or economic aid, they offer access to natural and strategic resources.

Support for the RSF

UAE supplies weapons, including advanced Chinese systems and drones, as well as intelligence and financial support.

Its relationship with the RSF originates from their gold trade.

Libya, Chad, South Sudan and the Central African Republic are used as transit hubs for resources coming from the UAE and other backers.

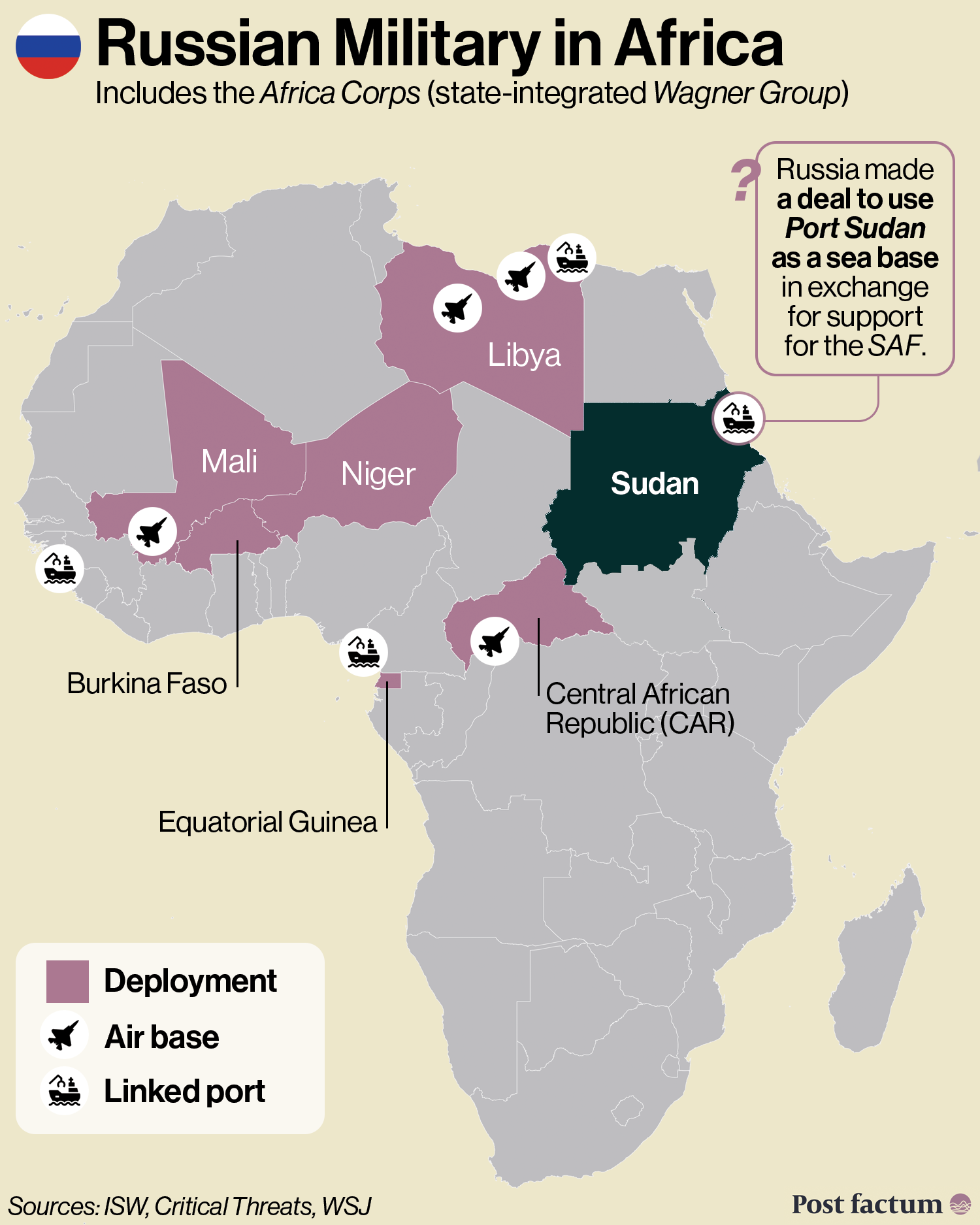

Russia supported the RSF through its mercenary Wagner Group, which was involved in illegal mining and providing security to local warlords.

Russia supplied drones and weapons to the RSF through Wagner-linked networks.

In 2024, Russia shifted its positionand started supporting the SAF.

In return, Sudan offered Russia a military base in Port Sudan, on the Red Sea.

It would become Russia’s first naval base in Africa.

Support for the SAF

Egypt supports the SAF, providing military aid and weapons.

Egypt mostly supports official state actors rather than armed groups across the region.

The RSF accused Egypt of carrying out airstrikes on its positions.

Iran supplies weapons to the SAF, including drones.

Iran is particularly interested in Sudan’s strategic positionon the Red Sea.

Türkiye supplies weapons and provides drone pilot training.

Military deliveries include Bayraktar TB2 drones and guided munitions.

Türkiye aims to expand its military and economic presence in Africa.

Ukraine deployed some of its special units in Sudan to conduct raids against the RSF and Russia’s Wagner Group.

The Wagner Group has since been integrated into Russia’s official military, which (as discussed) is no longer supporting the RSF.

Author Simone Chiusa

Editor Anton Kutuzov

Join Post factum Pro to access the comments section