Geopolitics of Drones

May 25, 2025

As of 2024, more than 100 countries use military drones.

Drones are reshaping how states think about airpower and battlefield dominance.

Traditionally, fighter jets represented air superiority.

They were seen as needed for gaining control of the skies and neutralising enemy airforce before it can respond.

But this model is being disrupted.

Fighter jets require highly trained pilots, complex maintenance, and careful risk calculation.

Drones can be used in large numbers, sacrificed in high-risk missions, and quickly replaced.

This shift transforms the concept of modern air power:

It does not make fighter jets obsolete. However, drones have reduced their centrality.

What are drones?

Drones, or UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles), are aircraft without a human pilot on board.

They can be remotely controlled or fly autonomously.

Initially, drones were developed to survey the battlefield and gather intelligence.

Their role expanded after 2001, especially in counterterrorism operations.

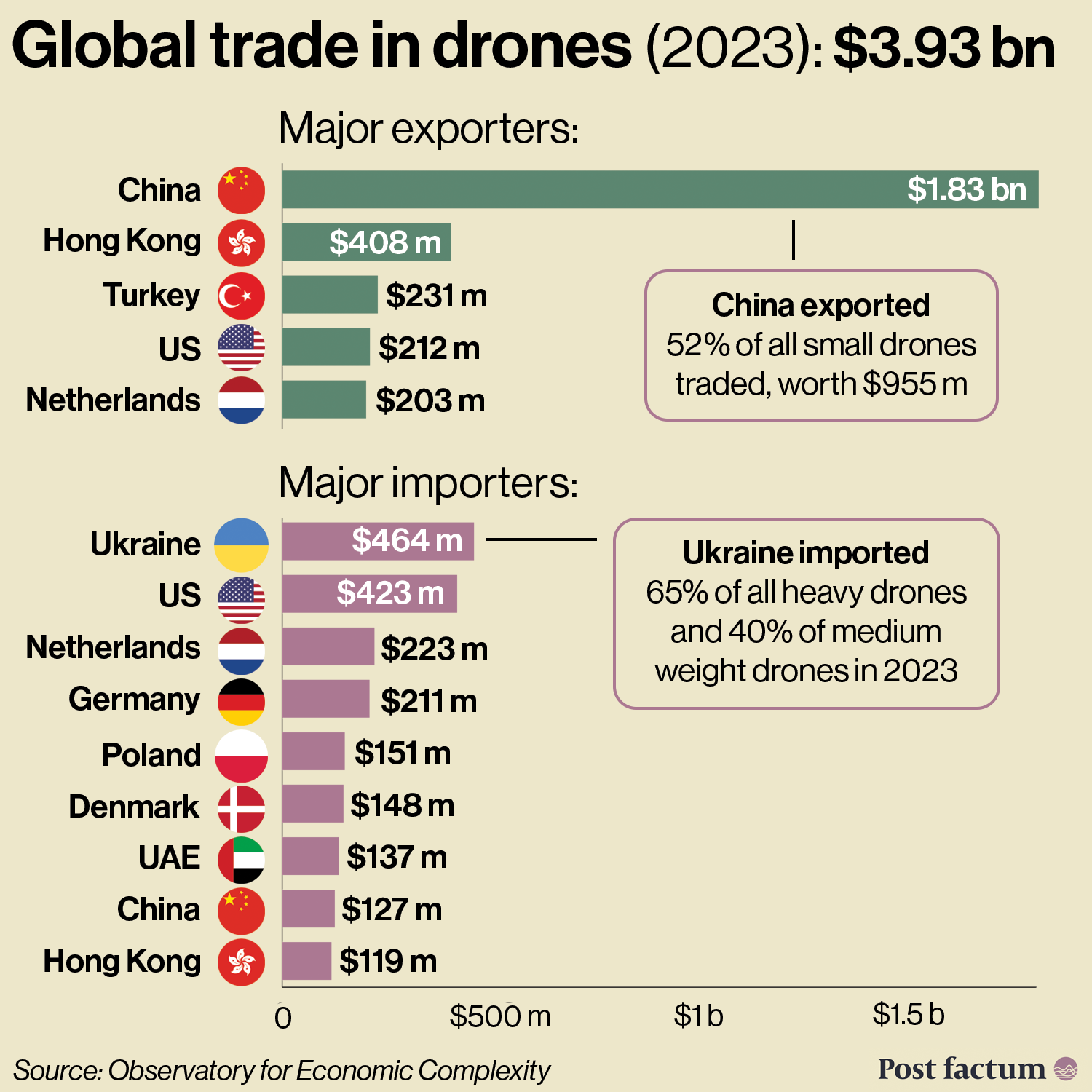

The global military drone market is projected to exceed $58 billion by 2030.

In comparison, the market for fighter jets is expected to reach $59 billion in the same year, while the tank market would grow to $7 billion.

Drones offer advantages over manned aircraft. They are smaller, cheaper, and easier to deploy.

Moreover, UAVs can fly for longer periods without refuelling.

They are more effective at surveillance and allow for more precise strikes than missiles or artillery.

Drones also offer political advantages:

Since no soldiers are put in danger, governments face less domestic pressure when authorising operations.

Drone warfare: a short history

Drones were first used in large-scale operations during the Vietnam War, when the United States deployed them for high-risk surveillance missions.

In the 1980s, Israel expanded drone capabilities by integrating them into electronic warfare and battlefield operations.

By the 1990s, drones became a routine part of US military strategy, providing live intelligence in operations such as the Gulf War.

The first lethal drone strike occurred in 2001, and drone-led counterterrorism expanded in the following decades.

Between 2009 and 2021, the United States Air Force conducted over 14,000 drone strikes across Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Iraq, Somalia, and Libya.

During the years, strikes eliminated high-value targets, including the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani (2020), as well as terror group commanders.

US drone strikes resulted in an estimated 8,858 to 16,901 deaths between 2010–2020, including both militants and civilians.

In Ukraine, drones are used on an unprecedented scale.

Both Russia and Ukraine deploy thousands of UAVs each month.

Most are low-cost commercial drones adapted for military use.

Drones offer airstrike power at low cost, allowing small units to carry out complex missions.

A basic First-Person View (FPV) drone is cheaper than an iPhone, costing as little as $300.

FPV drones are remotely piloted and stream live video directly into a headset worn by the operator. This gives the pilot a “first-person” perspective, as if they were inside the drone itself.

The immersive control allows for precise flying at low height, making these drones ideal for ‘suicide’ attacks or dropping munitions directly onto enemy targets.

As of May 2025, Russia has reportedly lost over 3,000 tanks, many of which to strikes with low-cost drones.

Land drones are increasingly used for logistics, mine clearance, and combat support.

Similarly, naval drones have emerged as tools for reconnaissance, and attacks on ships and port infrastructure.

Drones are now used in all types of warfare:

Offensively: striking vehicles, fortifications, and personnel

Defensively: exploring the field, guiding artillery fire, or hunting other drones.

What we are seeing is the rise of drone-centric warfare, with cheaper and more precise capabilities, and less direct human involvement.

United States

Drones are embedded in every layer of US military strategy.

The United States used drones extensively in:

Targeted killing operations

Surveillance and intelligence gathering

Protection, watching over troops and supply lines

Iran

Iran has made drones a key part of its asymmetric strategy, using them to counterbalance the superior airpower of its rivals and extend its regional influence.

Why Iran turned to drones?

In recent years, Iran has rapidly scaled up its drone production.

Estimates suggest it can produce around 150 drones per month.

Iran’s conventional military faces significant structural and geopolitical limitations:

International sanctions reduced its access to advanced aircraft tech and components.

Technological inferiority: Iran’s air force is behind those of regional rivals, like Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Regional encirclement: Surrounded by US bases and hostile neighbours, Iran faces constant pressure.

To overcome these constraints, Iran strategically invested in a domestic drone industry that is:

Cost-effective

Capable of long-range strikes

Capable of deployment by proxy groups

Iran’s drone fleet is one of the most combat-tested in the world.

Notably, Iranian Shahed drones have been widely used by Russian forces in Ukraine.

Israel

Israel began using UAVs in the early 1980s, and drone operations have since become part of its national defence doctrine.

Israel uses drones across multiple fronts for both surveillance and precision strikes.

In Gaza, drones are used for targeted killings, battlefield surveillance, and strike coordination against Hamas.

Along the northern border, drones monitor Hezbollah activity in Lebanon and Syria.

During recent escalations in the West Bank, drones were used for crowd monitoring, reconnaissance, and, increasingly, for strike missions.

Israel has also begun to integrate loitering munitions and AI-assisted targeting into its drone fleet, shortening reaction times between detection and engagement.

Israel is one of the world’s top drone exporters, with platforms sold to more than 50 countries.

For Israel, drone exports are also a key part of its defence diplomacy:

Sales of drones also lead to training, joint exercises, and intelligence-sharing agreements, strengthening Israel’s partnerships.

Turkey

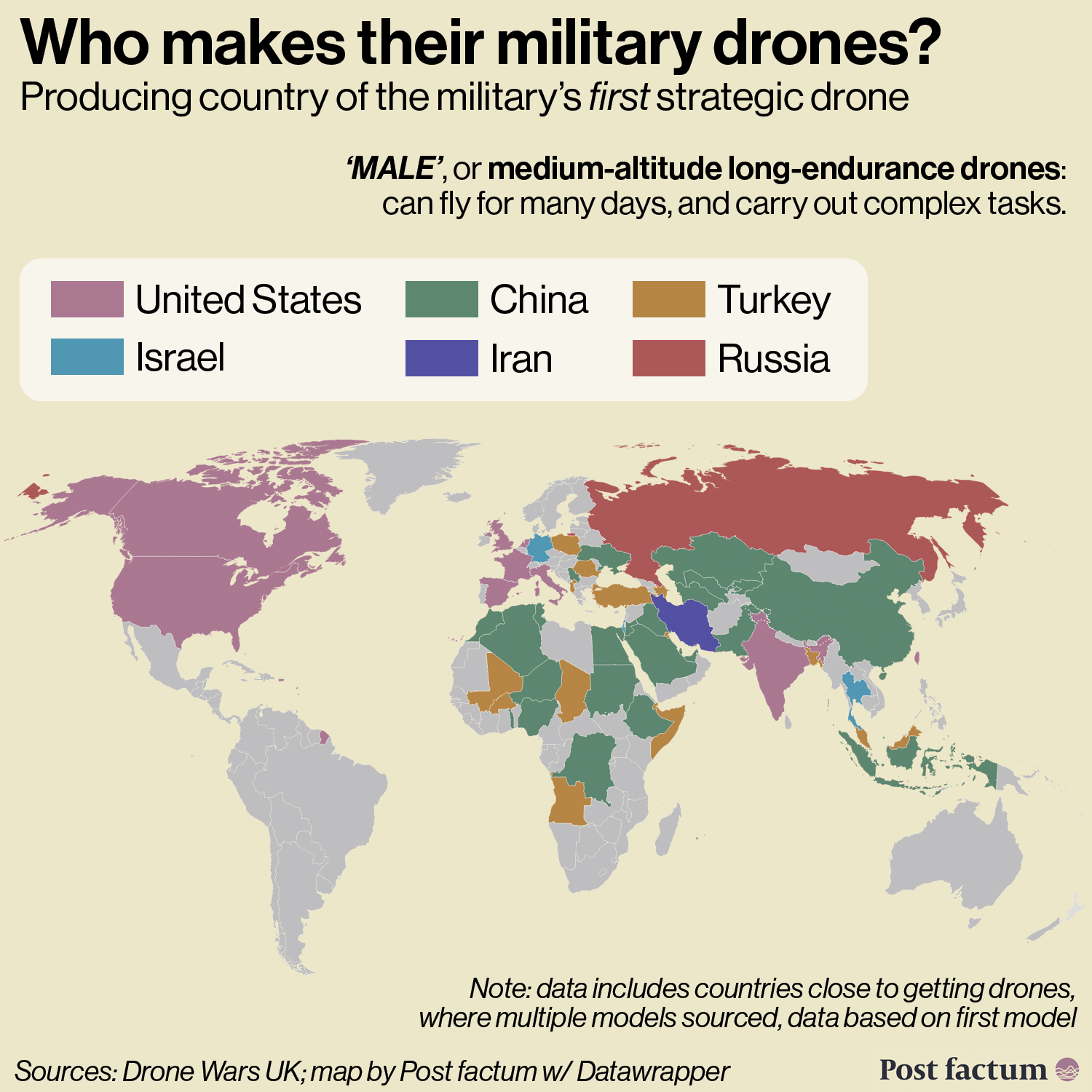

Turkey has emerged as one of the most influential drone powers of the 21st century.

Drones now form a central pillar of Turkish military doctrine and foreign policy.

Turkey’s drone program was born out of both necessity and ambition:

A need for effective tools in counterinsurgency campaigns against Kurdish groups, and in border security operations

Strategic ambition to gain greater defence autonomy and position itself as a global defence exporter

To achieve this, Turkey supported a domestic drone industry led by firms like Baykar.

Turkish UAVs have been used in multiple conflicts across the globe including by Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Turkey itself.

Turkey has become one of the leading global drone exporters.

Bayraktar TB2 has been exported to over 30 countries, including Ukraine, Poland and Pakistan.

Turkish drones are especially attractive to middle powers and developing nations due to their low cost and minimal export restrictions compared to US or Israeli systems.

Exports also enhancing Turkey’s defence partnerships.

Non-State actors and drones

The rapid expansion and declining cost of UAVs have enabled non-state actors to use and weaponise drones:

Hezbollah

Hezbollah has been developing its drone program with Iranian support since the early 2000s.

Iran has provided Hezbollah with UAV platforms, extending the group’s reach and creating pressure on Israel.

It extends Iran’s strategic reach without deploying its own forces

It allows Hezbollah to attack Israel with lower risk to itself

Israeli defence officials now treat Hezbollah’s drone program as a serious threat, due to its potential to overwhelm air defences by launching many drones at once.

Houthis

The Houthis have emerged as one of the most active non-state drone users.

They operate a fleet of drones modelled on Iranian ones.

Since 2018, Saudi Arabia has reported hundreds of drone attacks launched by the Houthi forces against airports, military bases and oil infrastructure.

Notably, in 2019, the group launched a coordinated drone attack on an oil facility, disrupting the extraction of 5.7 million barrels per day of Saudi oil, nearly 6% of global supply.

Since the beginning of the war in Gaza, the Houthis have extended their operations beyond Saudi Arabia.

They have launched long-range drones toward Israel, citing solidarity with Palestinians.

The rebel group has also targeted commercial ships transiting the Red Sea, threatening global maritime trade routes.

Mexican cartels

Between 2020 and 2022, Mexican security forces recorded over 100 incidents involving cartel-operated drones.

Cartels use drones for several reasons:

Monitoring police positions and roadblocks

Remote attacks

Ambush and intimidation against police forces or local communities

Smuggling narcotics across borders

Drone attacks have become a common threat posed by the cartels, both for law enforcement and rival groups.

The platforms used by Mexican cartels are typically commercial quadcopters, which could be modified to carry explosives or drugs.

Such drones cost a few thousand dollars and can be bought online.

Author Simone Chiusa

Editor Anton Kutuzov

You can help us secure our long-term future!

Please consider sending us a regular donation.

Find out more: